© Constance J. Moore

Colonel, ANC (Retired), ANCA Historian

The China-Burma-India (CBI) Theater was the forgotten part of World War WII. Assigned personnel complained that CBI was the last to be supplied, last to be planned for, and last to have a strong American medical system.

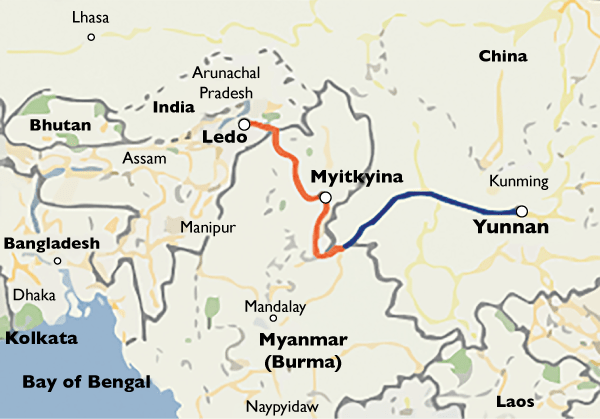

The Burma Road was the key avenue to supply and resupply the Chinese Army, who were allies of the United States. After the Japanese cut off the road, United States forces and native labor built a dirt highway, called the Ledo Road, as an alternative route. It started at Assam, India, snaked through the mountains and jungles of Burma and ended at a juncture with the Burma Road.

The Burma Road was the key avenue to supply and resupply the Chinese Army, who were allies of the United States. After the Japanese cut off the road, United States forces and native labor built a dirt highway, called the Ledo Road, as an alternative route. It started at Assam, India, snaked through the mountains and jungles of Burma and ended at a juncture with the Burma Road.

The 14th Evacuation Hospital was erected at mile 19 of the dirt highway in August 1943. When the hospital arrived, two wards and several staff barracks were erected. The wards were quite spacious, with ceiling and walls built of bamboo and covered with burlap to keep out the mosquitos.

The medical staff were challenged to keep the troops healthy with the lack of fresh fruits, vegatable and meat. Most patients also were severely dehydrated from typhus, malaria, amebic dysentery, and sheer exhaustion from the stress of living in a “hot and humid ... environmental conditions not conducive to good health.”1

During 14-18 hour shifts, each nurse and one to two corpsmen took care of between one hundred to one hundred-fifty patients. The work was physically draining. Most days they were drenched – not by the mansoons, but from perspiration. Nurses hated to go off shift because the patients were so desperately ill. The staff from the next shift often had to push them off the ward so the off-duty nursing personnel could get some rest. To help out, ambulatory patients were put to work. For the nurses and corpsmen, the extra hands were invaluable.

Lt. La Vonne Telshaw

and Interpreter |

With minimal supplies, the nurses improvised, using old boxes, and bamboo to create chart racks, dressing trays, and cabinets. Since they were not given any writing materials, nurses went to the bazaars and bought notebooks, pencils, ink, glue, rulers, and clips to create medical records.2

To obtain water, corpsmen had to walk off the units to fill buckets at the closest faucet. There was never enough warm water so cold baths generally were given late in the morning or early afternoon when the outside temperature was warmer.3

Initially, American and Chinese patients were housed together on the same unit. Because of different dietary needs, however, the Chinese were moved to their own wards so that their own cooks could provide meals for them. Interpreters helped explain medical procedures to the non-English speaking patients. Nurses learned important Chinese words, such as pain, medication, hello, and thank you.

When the hospital stood down in December 1945, the Army nurses took pride that they had cared for many hundreds of ill and injured personnel. Although many were homesick or worried about loved ones, they felt in their own way that they had helped to win the war.

1 BG Connie L. Slewitzke, USA (Ret.), “Foreword,” in LaVonne Telshaw Camp, Lingering Fever: A World War II Nurse’s Memoir (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 1997), 1.

2 Agness Egress, “the 14th Evac on the Ledo Road,” American Journal of Nursing 45, no. 9 (September 1945), 704.

3 Ibid.