© Constance J. Moore

Colonel, ANC (Retired), ANCA Historian

When the United States entered the World War in April 1917, American forces were ill-prepared to confront the horrors of chemical warfare. Mustard “gas,” particularly, was difficult to manage because of its characteristics and long life cycle. While true gases such as chlorine and phosgene dissipated over several hours, this agent (actually a liquid, dispersed in droplet or aerosol form) remains active for up to 25 to 30 years1 and causes rapid injury in contact with skin, even through clothing. Thus, after battles were concluded, even when the soldiers rested, ate food or slept, mustard gas remained dangerous. It is not surprising that mustard caused the largest number of chemical casualties in the war, and earned the sad title of the “King of Battle Gasses.”2

Once combatants were exposed to the agent, they needed immediate decontamination or within 30 minutes of exposure, huge blisters would spot their entire bodies.

3 The decontamination process required that soldiers were stripped of their uniforms, bathed and given new clothing to wear before they were brought to the hospital for treatment. Miss Julia Stimson (later to become Chief of the Army Nurse Corps) described the phenomenon: “We have been receiving patients that have been gassed and burned in a most mysterious way … they had burns on their bodies, on parts that are covered with clothing.”

4

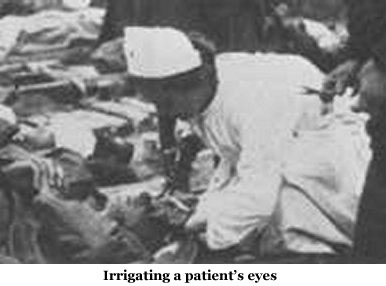

Several treatments were devised. Acute conjunctivitis required alkaline eye irrigations over and over again until the symptoms lessened and abated. With the large numbers of patients admitted to hospital units, this meant the nurses started at one end of the ward and by the time they had reached the other end of the unit, it was time to begin a new round of treatments.5 For those who had breathed in the mustard gas, nurses at Base Hospital 32 helped devise a mixture of “guiacol, camphor, menthol, oil of thyme and eucalyptus [that forced the patients to expectorate the inflammatory material]. Patients received immediate relief, [respirations were less labored so] … healing was begun.”6

Several treatments were devised. Acute conjunctivitis required alkaline eye irrigations over and over again until the symptoms lessened and abated. With the large numbers of patients admitted to hospital units, this meant the nurses started at one end of the ward and by the time they had reached the other end of the unit, it was time to begin a new round of treatments.5 For those who had breathed in the mustard gas, nurses at Base Hospital 32 helped devise a mixture of “guiacol, camphor, menthol, oil of thyme and eucalyptus [that forced the patients to expectorate the inflammatory material]. Patients received immediate relief, [respirations were less labored so] … healing was begun.”6

Chemically burned soldiers took longer to heal than thermally burned combatants.7 Simple burns were mostly treated with sodium hypochlorite on the wounds.8 More extensive burns were treated with Vaseline gauze.9 Nurses first excised blisters then wrapped the affected area. Chief Nurse Lily B. Craighton of Red Cross Military Hospital # 6 described how chemical burn treatment was performed in their hospital:

“The men would come in with hideous blisters, extending from their shoulder down [the length of their bodies]. The nurses would clip away all this blistered skin, clean the … raw surface with antiseptic solution, dry it with an electric blower and spray on the “amberine.” Burns treated in this way healed in an incredibly short time.”10

At the war’s end, more than 30% of the casualties were related to chemical warfare and 80% of the casualties were directly related to mustard gas.11 In creative and compassionate ways, Army nurses, as members of the busy healthcare team, rose to the challenge of caring for combatants who were injured by this hideous type of warfare weapon. Without their ingenuity, and dedicated service the majority of the gas cases would not have been successfully treated.12

- Robert Joy, “Historical Aspects of Medical Defense Against Chemical Warfare,” in Frederick Sidel, Ernest Takafuji and David Franz, editors, Medical Aspects of Chemical and Biological Warfare, (Washington, DC: The Borden Institute, 1997): 96.

- Gerard Fitzgerald, “Chemical Warfare and Medical Response During World War I,” American Journal of Public Health, 98 (April 2008): 4.

- Ibid: 5.

- Julia Stimson, Finding Themselves, (New York: The Macmillan Co., 1918): 80.

- Minnie Goodnow, War Nursing, (Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Co., 1918): 115.

- Alma Woolley, “A Hoosier Nurse in France: The World War I Diary of Maude Frances Essig,” Indiana Magazine of History, 82 (March 1986): 42.

- M. W. Ireland, The Medical Department of the United States Army in the World War, Vol. 14: Medical Aspects of Gas Warfare (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1926): 1821.

- Robert Joy, “Historical Aspects of Medical Defense Against Chemical Warfare,” in Frederick Sidel, Ernest Takafuji and David Franz, editors, Medical Aspects of Chemical and Biological Warfare, (Washington, DC: The Borden Institute, 1997): 100.

- M. W. Ireland, The Medical Department of the United States Army in the World War, Vol. 14: Medical Aspects of Gas Warfare (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1926): 1687.

- Lavinia Dock, History of the American Red Cross Nursing, (New York: The Macmillan Press, 1922): 611.

- Gerard Fitzgerald, “Chemical Warfare and Medical Response During World War I,” American Journal of Public Health, 98 (April 2008): 5.

- The number of fatalities for chemical casualties was quite low. For American forces it was 2% of all gas related injuries. As noted in: Robert Joy, “Historical Aspects of Medical Defense Against Chemical Warfare,” in Frederick Sidel, Ernest Takafuji and David Franz, editors, Medical Aspects of Chemical and Biological Warfare, (Washington, DC: The Borden Institute, 1997): 101.