© Constance J. Moore

Colonel, ANC (Retired), ANCA Historian

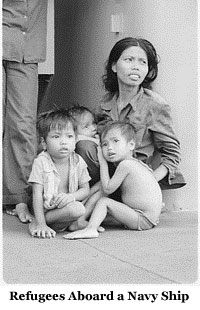

After the fall of Saigon in 1975, the largest refugee movement in American history occurred. From April to December of that year, more than 140,0001 people moved from Southeast Asia in a two-phase process called Operation New Life/New Arrival. This article, which focuses on Operation New Life, is part one of a two-part discussion about the impact of Army nurses on the health care of the evacuees. This paper focuses on the evacuation of the people to one of the island staging centers, Orote Point on Guam.

With the massive waves of refugees threatening to overwhelm the housing and quarters of the Guam's naval base by mid-April 1975, military officials decided to build a huge camp on an abandoned World War II airstrip. Navy SeaBee crews bulldozed and cleared 500 acres of brush and prepared "pads" to accommodate 2,500-3,000 tents on Orote Point. During the next 60 days, this camp, commonly called Tent City," reached a peak population of 39,000, and processed more than 90,000, or two out of every three refugees who left Southeast Asia.2

With the massive waves of refugees threatening to overwhelm the housing and quarters of the Guam's naval base by mid-April 1975, military officials decided to build a huge camp on an abandoned World War II airstrip. Navy SeaBee crews bulldozed and cleared 500 acres of brush and prepared "pads" to accommodate 2,500-3,000 tents on Orote Point. During the next 60 days, this camp, commonly called Tent City," reached a peak population of 39,000, and processed more than 90,000, or two out of every three refugees who left Southeast Asia.2

To provide health care for the refugees in Tent City, Army medical leaders tasked the 1st Medical Group from Fort Sam Houston, Texas. By the time the organization was operational, on 30 April 1975, Orote Point already was sheltering more than 16,000 evacuees3 and was growing each day. Along with Lieutenant Colonel Jeanne Hoppe, the Chief Nurse, were assigned eight Army nurses to handle the mission. The majority of the nurses worked in field dispensaries or small ambulatory hospitals that handled both outpatient and inpatient care. These tent facilities were positioned in separate locations to be readily available for evacuees. Their medical caseload was significantly higher than medical units at other staging centers. The majority of their cases were children under the age of 16 years.4

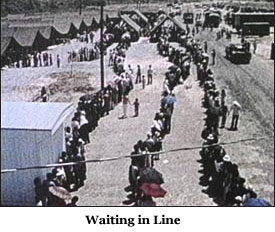

Perhaps the biggest worry for medical personnel was the primitive nature of camp life, where refugees stood in the sun and suffered from the flies and mosquitoes while they waited in long lines to eat, to receive additional clothing, to be processed by immigration, or to be assigned to sponsoring organizations. These people, moreover, were packed 30 to 40 people in hot tents, using outdoor toilets that were generally clogged and unsanitary, a problem that was never resolved despite the Herculean efforts of the Preventive Medicine people.5 How could two Community Health Nurses, Lieutenant Colonel Anna Frederico and Captain Mary Criswell, handle public health issues of such a mammoth camp? Their chief, Colonel Hoppe, reached out to the Guam Red Cross6, which identified volunteers from the community and the local university. As a result, each day volunteer nurses, including religious missionary nuns, Australian and local nurses, college instructors and students, came to assist with the massive effort.

Perhaps the biggest worry for medical personnel was the primitive nature of camp life, where refugees stood in the sun and suffered from the flies and mosquitoes while they waited in long lines to eat, to receive additional clothing, to be processed by immigration, or to be assigned to sponsoring organizations. These people, moreover, were packed 30 to 40 people in hot tents, using outdoor toilets that were generally clogged and unsanitary, a problem that was never resolved despite the Herculean efforts of the Preventive Medicine people.5 How could two Community Health Nurses, Lieutenant Colonel Anna Frederico and Captain Mary Criswell, handle public health issues of such a mammoth camp? Their chief, Colonel Hoppe, reached out to the Guam Red Cross6, which identified volunteers from the community and the local university. As a result, each day volunteer nurses, including religious missionary nuns, Australian and local nurses, college instructors and students, came to assist with the massive effort.

Volunteers were assigned to visit individual tents where they could assess the health status of the occupants.7 The nurses and nursing students specifically watched for signs of dehydration, and conjunctivitis, which had reached epidemic proportions at one point during the operation. After the first few visits, student nurses improvised their own medical packs — filled with band-aids, antibiotic creams and other medical supplies — so they were prepared to meet the basic health needs of the community.8

Since 18% of the population was under the age of six years9, the community health nurses helped establish Baby Care Centers, where evacuees could obtain disposable diapers, baby formula, baby food, soap and toilet tissue. These special tents were dispersed throughout the camp for the convenience of the refugees. These health care professionals provided rudimentary training to the non-medical service members who manned the supply centers. In essence, these military personnel were nurse-extenders" who helped identify refugees at risk.

When the flag was lowered on 24 June 197510, and the last refugee had left the island, Army nurses packed their bags to return home. Despite the unresolved problem with the sanitation system, the medical care provided for the refugees was considered excellent.11 The success of the refugee evacuation to Guam's staging centers was due to the cooperation between the U.S. military, the local community and the island residents — many of whom volunteered at the refugee camps to provide medical treatment. The Army Nurse Corps officers helped to facilitate this success by their "can do," creative leadership, so that the health needs of the refugees were met.

- U. S. General Accounting Office. Evacuation and Temporary Care Afforded Indochinese Refugees--Operation New Life (Washington, DC: Comptroller of the United States, General Accounting Office, 1976): Cover letter to the President of the United States.

- George Gonsalves, Operation New Life: Camp Orote—A Study in Refugee Control and Administration, Doctrine and Practice (Fort Leavenworth: Defense Technical Information Center, 1976): Abstract.

- Ibid, 18.

- Mary Sarnecky, A Contemporary History of the Army Nurse Corps (Washington, DC: The Borden Institute, 2010): 146.

- George Gonsalves, Operation New Life: Camp Orote—A Study in Refugee Control and Administration, Doctrine and Practice (Fort Leavenworth: Defense Technical Information Center, 1976): 92.

- Ibid,146; Sally Tsuda, “Vietnamese Evacuee Camp: A learning Experience,” Nursing Outlook 23 (September 1975): 563.

- Ibid, 161; Sally Tsuda, “Vietnamese Evacuee Camp: A learning Experience,” Nursing Outlook 23 (September 1975): 564.

- Sally Tsuda, “Vietnamese Evacuee Camp: A learning Experience,” Nursing Outlook 23 (September 1975): 563.

- George Gonsalves, Operation New Life: Camp Orote—A Study in Refugee Control and Administration, Doctrine and Practice (Fort Leavenworth: Defense Technical Information Center, 1976): 42.

- Ibid, 82.

- Ibid, 104.